The art (and science) of persuasion

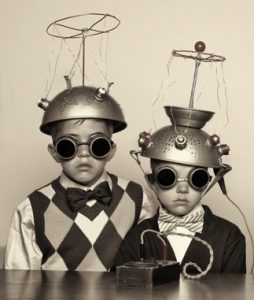

Using science to get into the customer’s brain

One of the most interesting new business pitches I was ever involved in was when a prospective B2B client, a large and well-known electronics company, was trying to introduce a new product line. The problem was, these new products were very different from those that the company was well known for.

The client had spent considerable sums introducing the new line, yet had made little headway in the market. So they opened this assignment to other agencies.

We were briefed, we developed creative, and we took it to a focus group. The creative bombed, badly. But why it bombed was the same reason the product line was getting so little traction — in the mind of the customer, these new products just didn’t fit with the way they perceived the company.

Well, we quickly regrouped and developed new creative. But this time, rather than just introduce the new products, we built a connection between them and the products the company was known for. The new creative worked well, helping to create an “aha” moment with people in the second focus group.

In our final presentation to the client, we took them through our experience, even showing the creative that bombed. Not only did we win the work for the new product line, we became agency-of-record for the entire account. We also learned a valuable lesson in the art of persuasion.

We called it, “meeting the audience at its mindset.”

If you look up “Persuasion” in Wikipedia, you’ll find a good article on the subject and how it applies to what we do as communicators. You’ll learn about the two processes of persuasion: systematic and heuristic. Systematic persuasion appeals to logic and reason, and is more often used in B2B advertising. Heuristic persuasion appeals to habit and emotion, most often found in B2C. And of course, a lot of advertising blends elements of both.

The article also covers the six principles of influence delineated in Robert Cialdini’s book Influence, which discussing principles and processes that you’ll recognize in your day-to-day work.

The Wikipedia article also covers the “Social Judgment Theory,” which applies to the new business pitch experience mentioned earlier. It’s about how we sort, accept or reject new information. If that information is contrary to our beliefs, we have a hard time accepting it. Unless the new information is presented as a step forward from where we are, as opposed to a big leap, it tends to fall on deaf ears.

Another interesting section, “Neurobiology of Persuasion,” deals with how our brains are wired to react to information. It also helps explain the physiology of what’s happening in “Social Judgment.” If the information falls in the so-called pleasant zone of our brain, it creates a positive association, which is why celebrities are so often successful in advertising. If it falls in the indifferent or negative zone, we are more likely to reject it. In fact, totally different parts of the brain react when presented with what it perceives as positive or negative information.

There is however, a complication — different people can perceive the same words differently. The use of “new and improved” in product advertising is an example. For younger audiences these words tend to fall in the positive zone. But for older audiences, the words may, at best, fall into the zone of indifference.

We saw some of these mind games play out during the ’08 presidential election. Obama offered hope and change and used a symbol of a sunrise. McCain presented himself as someone who offered safety and security, and used a gold star symbol of his military service. By and large, the young flocked to Obama and older voters went for McCain. Of course, other factors determined the eventual outcome of the election, but from an advertising perspective we can see who the candidates were directing their appeals to.

As creative people, we tend to think of persuasion as an art. But it’s important to be aware of the science behind it, as well.